Happy Friday Chicago!

Today is a special edition of Still Gotta Come Through Chicago.

Chicago’s Sports Historian (and newsletter reader) Jack Silverstein pitched me on running the below story about a month ago. I’ve never run a guest post before, but I thought this would be a great changeup for the newsletter this week.

Everything Silverstein writes is great. He has a book out, Why We Root: Mad Obsessions of a Chicago Sports Fan, which is available everywhere, including Amazon. He is working on the first full book on the 90s Bulls, with his research and interviews available on his Substack. If you enjoy today’s newsletter, you can also check out some of his other work, including his: Twitter threads; his Wordpress; his writing at Windy City Gridiron; and my personal favorite, his mini book on the 1996 Chicago Bulls.

I’m grateful Silverstein thought of us for his latest piece, which covers a Chicago-related football topic I guarantee you know nothing about.

I’ll see you all next week.

How Chicagoan Arch Ward changed NFL history

The name of this newsletter is Still Gotta Come Through Chicago.

And when Arch Ward was sports editor of the Chicago Tribune, college football’s finest players had to come through Chicago. So did the world’s best amateur boxers. So did MLB’s all-stars. After World War II, a whole other pro football league was founded in Chicago.

Because of that league, and a recent decision from NFL owners, Tom Brady is no longer the only quarterback in NFL history with seven championships.

George Halas, Curly Lambeau and Bill Belichick no longer have the most NFL championships as a head coach.

The NFL’s longest championship run is no longer a three-peat — it’s a five-peat.

The 1972 Dolphins are no longer the only undefeated champion in NFL history.

Say hello to Otto Graham, Paul Brown and the Cleveland Browns dynasty, including their undefeated 1948 club — all of whom can thank Chicago’s Arch Ward for their honors.

NFL owners in April voted to officially incorporate records and statistics from the All-America Football Conference into the NFL record book. The AAFC, sometimes called the AAC for All-America Conference, played four seasons after World War II, from 1946 to 1949, as both a challenger to the NFL and a potential partner in a World Series-style title. The new league re-integrated pro football, brought pro football to the West Coast, beat the NFL in average attendance and set off a high-stakes players bidding war, all leading to a truce in 1950, with the NFL absorbing three AAFC teams, most notably the four-time champion Cleveland Browns and the explosive San Francisco 49ers.

The creator of the league? Arch Ward, perhaps the most innovative newspaperman ever, as long as the innovations were not confined to the printed word.

“This is an announcement of the organization of the All-America Football conference, a new major professional league which will begin operation in 1945,” Ward wrote in the Tribune on September 3, 1944. “All clubs are financed by men of millionaire incomes who are prepared to engage in a battle of dollars with the National Football league, if necessary.”

This was the latest of many bold strokes from Ward, who viewed his role at the World’s Greatest Newspaper as a combination of news reporter and news maker. As Tribune sports editor from 1930 until his death in 1955, Ward would invent an event, use the Tribune to market the event, and then cover the event to further legitimize it.

His vision always involved creating dream matchups across leagues. In 1928, when he was a Tribune sportswriter, Ward drove the nation’s first intercity Golden Gloves battle between Chicago and New York, and then brought Golden Gloves international, starting with French boxers coming to Chicago in 1931. In 1933, looking to bring sporting excitement to the World’s Fair in Chicago, Ward pulled off a coup long thought impossible: a baseball exhibition between the best players of the National League and the best players of the American League.

That inaugural MLB All-Star Game was played at Comiskey Park and goes to this day, returning to Ward's Chicago in 2027 at Wrigley Field.

Seeking a follow-up for the World’s Fair as it stretched into 1934, Ward created another opportunity for fans and writers to answer a nagging “what if”: what if the best NFL team played the best college players? At a time when football fans weren’t all in on the so-called “post-graduate game,” Ward created the Chicago College All-Star Game, in which the defending NFL champion battled the best players from the previous collegiate season.

That inaugural game was played at Soldier Field, as were nearly all of the college all-star games until the final one in 1976.

The college all-star game quickly became the unofficial kickoff to each NFL season. The league saw its power and offered Ward the job of NFL commissioner. He declined, and in 1944 announced his own league instead.

“Go get a football and come back to talk to me,” NFL commissioner Elmer Layden said later. But Ward’s new league had something no burgeoning league ever had: access to an eager press. As not only sports editor but author of the Tribune’s influential “In the Wake of the News” column, Ward ensured that the AAFC got all of the press it needed.

“Ward was … a promotional genius who could turn a mere idea into success, as he had proved with the All-Star games in professional baseball and football,” Paul Brown wrote in his 1979 autobiography, and perhaps no move in his career epitomizes Ward’s fusing of newspaper man and promoter than bringing Paul Brown to the AAFC.

Ward conceived of the league, plotted out the markets and found the money men to fund the franchises. Among the markets would be Cleveland, from which NFL owner Dan Reeves of the Cleveland Rams wanted to escape. Ward convinced Cleveland taxi cab magnate Arthur “Mickey” McBride that Cleveland could support a second team, and then personally pursued Ohio State coach Paul Brown to run it.

Brown was an Ohio legend whose success and name recognition made him a natural candidate to launch a new club in a new league. Born and raised in Ohio, Brown played and later coached at the historic Massillon High School, winning five state championships and four national championships.

He then led Ohio State to their first ever national championship; after three years with the Buckeyes, he headed to the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Chicago, where he coached all-everything fullback Marion Motley.

“Arch visited me several times at Great Lakes after the AAC’s formation had been announced in 1944,” Brown wrote. “He laid down his idea, citing the tremendous financial resources available from the prospective owners, as well as his own ideas about the two major football leagues. He played to my ego as well, and without actually realizing it, he started me thinking that perhaps I should think of coaching where my talents would be appreciated and I would be welcomed.”

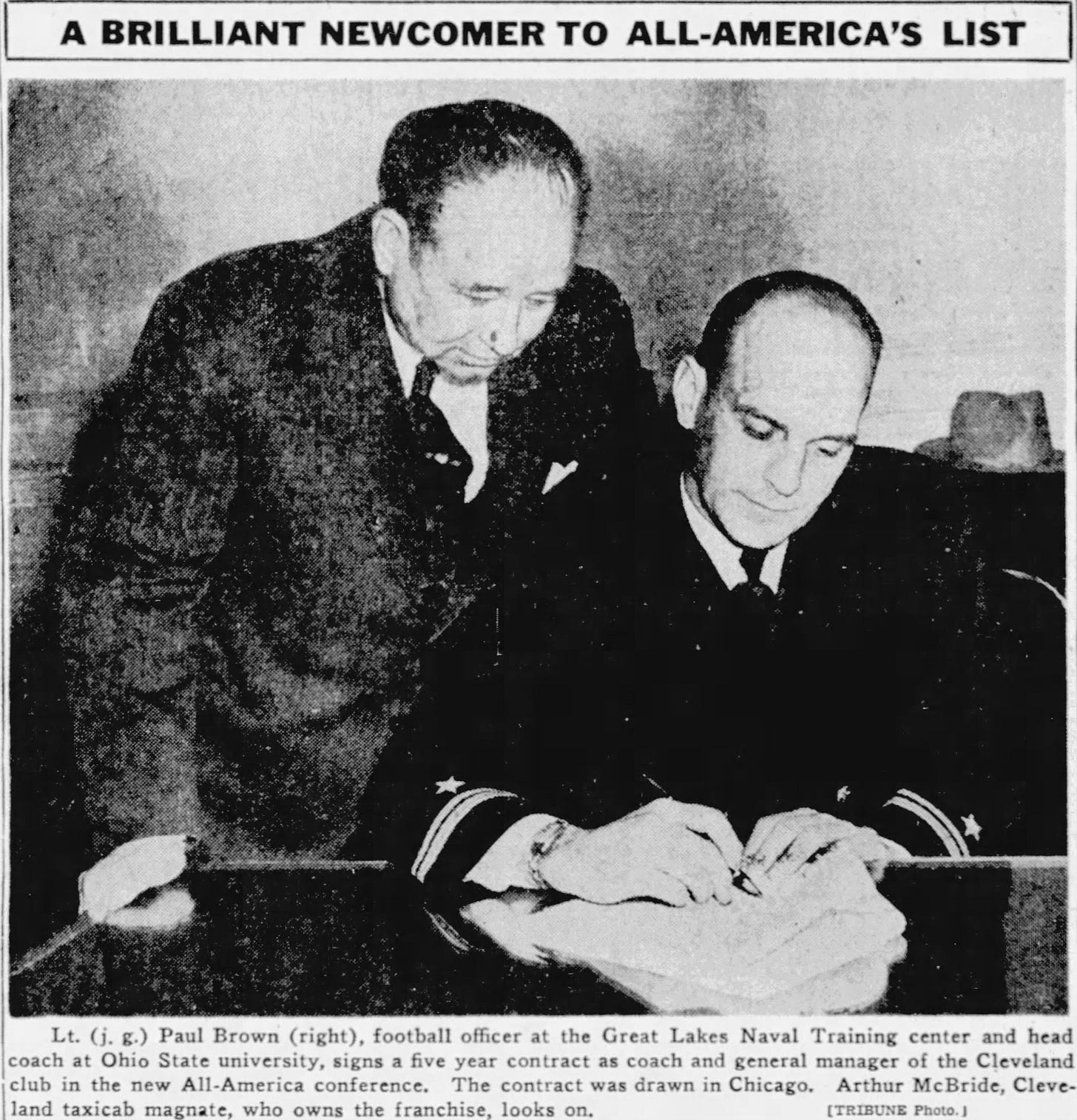

On February 8, 1945, Football League Founder Arch Ward brought Brown and McBride together at the Tribune, drew up Brown’s contract (somehow, he even had McBride’s power of attorney) and had Brown and McBride sign it in his office. And then he handed things off to Sports Editor Arch Ward, who wrote up the scoop in the Trib under a banner headline he no-doubt wrote too: “PAUL BROWN NAMED CLEVELAND PRO COACH.”

The Browns dominated, winning all four AAFC championships behind loads of talent, including Hall of Famers Otto Graham at quarterback and Motley at fullback. In 1948 they even achieved something that no NFL team had done: an undefeated, un-tied champion.

When the Browns moved to the NFL in 1950, they had to prove themselves all over again — and they did, winning a fifth straight championship. Now that their AAFC seasons count as de facto NFL seasons, the Browns leapfrog the 1929-1931 Packers and the 1965-1967 Packers for the NFL record for consecutive championships.

The AAFC’s legacy also includes its role in ending the NFL’s 12-year ban on Black players. When the Rams relocated to Los Angeles and wanted to play at the publicly funded Los Angeles Coliseum, activists, organizers and journalists in L.A. forced the Rams to integrate in order to use the stadium. So in the spring of 1946, the Rams signed former UCLA stars Kenny Washington and then Woody Strode. Over in the AAFC, the new Cleveland club came integrated, with Paul Brown signing his former star Marion Motley and fellow future Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee Bill Willis.

And just like that, professional football’s shameful ban was over.

The Browns reached the NFL championship game in ‘51, ‘52 and ‘53, losing them all, but then won in ‘54 and ‘55, all led by Graham, who retired with one of the greatest quarterback careers pro football has ever seen: 10 seasons, 10 championship appearances, seven titles.

No QB has surpassed those marks, though one finally did tie: Tom Brady, with his 10 Super Bowl starts and seven wins. Those are Super Bowl records, but as simply “NFL championships,” Brady’s seven rings and 10 title appearances tie him with Graham.

Few NFL coaches have as great a resume as Paul Brown, whose seven championships ranks first all-time… provided, of course, that you include his four AAFC titles. With them, Brown now sits alone above Halas, Lambeau and Belichick for the most “NFL” championships. In 2025, when the final undefeated team loses, the ‘72 Dolphins won’t be the only club whose perfect mark gets no more company.

And it all started with a sports editor in Chicago who dreamed big and executed bigger.

“The peace arrangement between the National Football league and the All-America conference,” Ward wrote on Dec. 12, 1949, “which has produced a new league to be known as the National-American Football league, should bring order to a sport that has been in a muddled condition for too long.”

Ward was wrong about the new name: the NFL would abandon the “NAF” name before the 1950 season even started. And though Ward was not technically wrong that the merger would bring a “world championship” game between the two sides, he was wrong about which sides, which merger and which date: the NFL-AFL championship game after the 1966 season, 11 years after Ward’s death, would become Super Bowl I.

But in that 1949 column he nailed one thing for sure: “Pro football,” he wrote, “will prosper.”

So it did. And even considering his rivalry with Halas and the NFL, I’m sure Ward would like to see a day soon when the road to the Super Bowl runs through Chicago. A civic booster’s job is never done.

Jack Silverstein is Chicago’s Sports Historian, a contributor to PFHOF voter Clark Judge’s site Talk of Fame and author of “Why We Root: Mad Obsessions of a Chicago Sports Fan.” Follow his 1990s Bulls book at readjack.substack.com.

Thank you for reading this special edition of Still Gotta Come Through Chicago. We’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programming next week. Thanks again to Silverstein for contributing to the newsletter. Comment below!

I actually learned a lot there. I also thought Paul Brown had coached at Miami University but I see he actually played there. I do know that he, in later years, became the President of the Board for Miami University and your grandfather had to work with him frequently and spoke very highly of him.

I never retained that Cleveland had just joined the league when they won the championship in 1950 or that Otto Graham was so prolific.

Jack is the most knowledgeable sports historian out there. He has been quoted in several sports history books. His groundbreaking investigation and story that revealed for the first time NFL owners ban of talented Black footballers from the 1920s - 1940s made national news, covered by major U.S. media (including CBS Sports, ESPN etc.). Hooray for Jack setting the record straight.